Search News

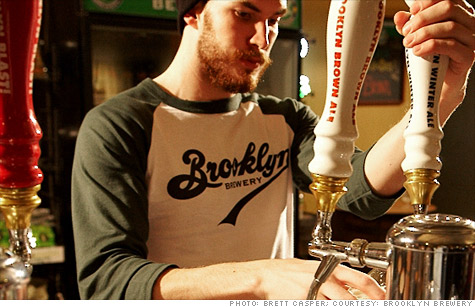

Stephen Hindy's Brooklyn Brewery set up shop in a 1890s factory called Hecla Ironworks.

FORTUNE -- When Stephen Hindy opened a beer brewery in Brooklyn's then-scruffy Williamsburg neighborhood more than a dozen years ago, he was on the front edge of a wave of smaller businesses that were returning to inner cities to tap the benefits of low rent, convenient locations, and ready labor.

He set up shop in a 1890s factory called Hecla Ironworks. In the era when Hecla was making railings and other ornamental iron for buildings, Williamsburg also boasted dozens of breweries. But as traditional manufacturing began to shrink, many companies folded or left the city, and, by the time Brooklyn Brewery arrived, the area was strewn with empty buildings and warehouses.

Today, Brooklyn has a completely different, largely revitalized face, but many cities are still contending with swaths of vacant industrial space. Over the next decade, in fact, more than one billion feet of industrial space in urban areas will be available, according to estimates from the Initiative for a Competitive Inner City, a non-profit group which highlights 100 fast-growing inner city businesses every year as part of its Inner City 100 ranking.

ICIC projects that there will be a demand from light industry and other companies for an almost equal amount of space -- about one billion square feet -- over the same time period. This year, the demand for industrial space is at historic averages -- between 1% and 2% -- and is projected to pick up later in the year, according to the 2012 Industrial Space Demand Forecast, by the NAIOP Research Foundation.

Going where the customers (and workers) are

Companies that choose to locate in the inner city often cite customer proximity as a primary motivator. The notion makes sense, as more people move to the cities, in the U.S. and abroad. Despite its name, Brooklyn Brewery beer was not initially produced and bottled in Brooklyn, but nearly 200 miles away in Utica, N.Y., at a local brewery there.

"We wanted to be close to our customers," recalls Hindy, who learned to brew beer in bathtubs when he was a foreign correspondent in the Middle East.

When the brewery began operations in Brooklyn, he says, "we had a van with our logo. We filled it with beer and peddled it to bar owners and restaurants all day, until we emptied the van."

This year, Brooklyn Brewery was ranked No. 67 on ICIC's list of the 100 fastest growing inner city companies. The company met ICIC's criteria, which require eligible companies to be located in the inner city, have 10 or more full-time employees, and a five-year operating sales history that includes at least $1 million in sales in its most recent year.

Boston-based ICIC, which has been ranking companies for 14 years, says that the companies it has selected for its annual list employ more than 100,000 people overall, of which some 40% are inner city residents. The ICIC's research shows that these companies hire disproportionately more nearby residents, unlike regional employers, which tend take on fewer inner city residents.

The 100 companies selected for the 2012 ranking generate more than $2.1 billion in sales per year, money that goes to local purchases and to employ local residents who might not have the flexibility or training to move elsewhere for a job.

Brooklyn Brewery has 60 workers at its 75,000-square foot Brooklyn site, and another 120 people tending to its upstate operations.

"Most of our employees live in Brooklyn, and come by bicycle or public transportation," says Hindy.

The company also uses nearby deep-water ports, most of which are located in large cities, to ship its Belgian-style corked beer to Europe, he says.

Plenty of cheap space to go around

About the same time the brewery was settling in Brooklyn, Rohit Patel, a computer and electrical engineer, was looking for a home for his infrastructure technology and telecoms security business. He too settled on a distressed city location, in a rundown manufacturing area in downtown Baltimore.

He started Intelect Corp. in a former broom factory, which was being used as business incubator space. In return for lower rent, tenants made improvements like putting in new electrical wiring, drywall, and ceiling tile.

His biggest battle was graffiti on the building, which he immediately had painted over -- and it stopped after two years. Business was growing so much that Patel says, "Five years later, our desks were crammed together." Instead of clearing out for the suburbs for more space, Patel purchased a building in the same neighborhood, a few blocks away, that had previously been used as a beer brewery and later a factory producing artificial flowers -- until the manufacturing moved offshore.

Patel now has 50,000 square feet that he has overhauled for offices, laboratories, and cable and wire manufacturing. About half of his 85-person workforce comes from the inner city. He also has about 40 part-time employees, about 80% coming from nearby neighborhoods.

"Our location means we can serve a lot of customers, because we are close to major highways and near major markets like Philadelphia and Washington, D.C.

In search of specialty space

Tammy Tedesco's Detroit catering company, Edibles Rex, hires 75% of its 76 employees locally. About 11 years ago, she located the company in a rundown area because she needed an adequately sized commercial kitchen to produce food, which includes lunches for school children.

The kitchen was in a hospital that had closed down, and now hosts a mix of businesses. Most employees commute by bus, a practice she believes will continue when the firm moves to a new home in the city's eastern market.

"We've outgrown the space we are in but we can't find a commissary kitchen to rent," she says. So her company has bought a 50,000-square foot building, which once housed a meat company, and plans to refurbish part of it and partially rebuild it to meet the company's needs. She is hoping that business continues to grow, and she will be able to expand to two shifts a day, and hire more local workers.

The price you pay for a river view

Lower rent and short-term leases attracted R. Bruce Wilson to choose the location for Cellular Specialties, which sells indoor wireless connectivity products and services. He decided on the old Amoskeag Millyard in Manchester, N.H. The mills, once a major producer of cotton textiles in the 19th century, occupy 5 million square feet on the Merrimack River.

The buildings were later reclaimed and rented. One of those buildings was turned into a business incubator, which is where Wilson started his company in 1997. After his business grew, he decided to remain in the complex, renting 25,000 square feet in one building, and some storage in another mill building, because "the space was less expensive and near downtown."

The location also is convenient for his 180 employees. About 140 of them commute into Manchester, but there is a downside. Like nearly all such buildings, the mill complex lacks an indoor parking garage and people have to vie for on-street parking.

As demand has risen for such repurposed properties, Wilson notes that he "pays a premium now for the river view."

"The bones of the building are lovely, with big, tall windows and hardwood floors," Wilson adds. But, renting without a river view, he says, "definitely would be cheaper."

When rents spike, relocating can be wrenching for a business. Brooklyn's gentrification has meant soaring rents and scarce space, which greatly complicated Hindy's search for a new spot for his growing brewery.

"We are an attraction because thousands of people come by for the brewery tour, and to taste our beer," he notes. Revenues from tours and tastings offset the rent.

And, Hindy says, "we bring importers and distributors to see the brewery, so we need to be in Brooklyn, not somewhere else." ![]()